A Fano, A Fano, A Fano ra!

One afternoon, I looked up from Swell’s foredeck and thought my eyes were fooling me. I rubbed them with my fists, then looked again. I was currently reading “We the Navigators” by David Lewis, about the marvels of ancient navigation in the Pacific, and there, plain as day, came 5 traditional Polynesian sailing canoes!?

I’d actually heard about, Tavaru, a privately funded project to revive and celebrate the cultures and traditional navigation techniques among the peoples of the Pacific. There goal was to learn to sail the canoes this year through trips around the Pacific, and then unite the following year to sail up to Hawaii and protest the Naval activity that are disturbs marine mammal sonar. There were canoes from Tahiti, New Zealand, Fiji, Samoa, and the Cook Islands. Each had sailed there using only traditional navigation techniques. With neither GPS, compass, nor sextant, the crews of these ‘vakas’ (they were all modeled off the traditional Cook Islands design called a ‘vaka’) were using the land-finding techniques of their forefathers, who steered by the sun, stars and moon, swell patterns and wave refraction, winds, clouds, and birds. They’d already come from as far as New Zealand, Fiji, and Samoa! Although many gaps and mysteries exist in the precise history of how and when the Pacific Islands were populated, it is certain that the navigators of these amazing sea-crafts were not just steering on a whim. Not only did they successfully get their peoples, plants, pigs, etc.. to new islands, both archeological evidence and oral history attest to repeated trips to and from distant island groups long after settlement.

During my time in the Pacific, I’d developed a profound fascination and appreciation for this type of navigation, so I was thrilled meet the people and see the crafts involved up close. The ‘vakas’ were extraordinarily beautiful: fiberglass hulls with gorgeous wooden decks and masts. A small captain’s cabin arched between the two hulls, which were lined inside with bunks for up to 15 crewpersons. They took 3-hour shifts of 5-6 people trading off at the big wooden steering oar astern.

Although I wished they could have stayed longer, I paddled over to the Cook Islanders’ vaka, Marumaru Atua, for the hour before they left. They’d received the symbol of a good departure, a rainbow in the west, and so the fleet would sail for Rarotonga that afternoon. They invited me to share in a meal of taro, beans, fish, and corned beef, then everyone gathered atop the decks and joined hands in a parting prayer. Although I couldn’t understand exactly what he said in Cook Islander Maori, I could feel it perfectly. As they raised their anchors, I wished the crew my best tidings and gave them a fishing lure I’d made for their trip. As I paddled back to Swell on my longboard, I felt renewed confidence and enthusiasm for my next passage. Maybe some of the ‘mana’, or ‘spirit’ of the ancient navigators that was with the crew of the Marumaru Atua had rubbed off on me.

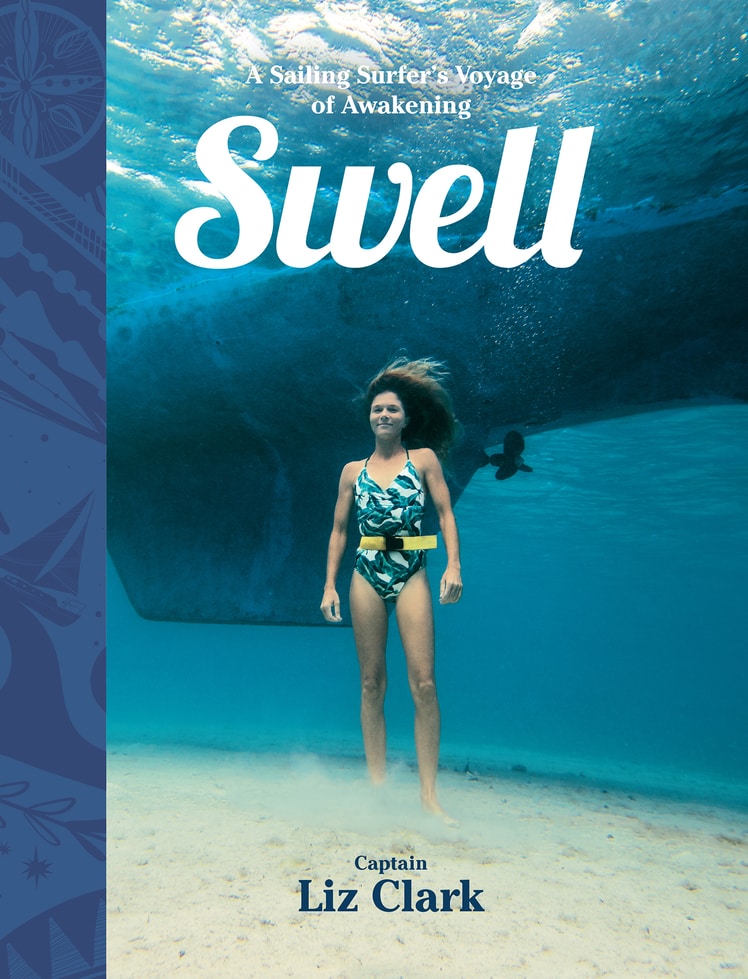

A fano, a fano, a fano ra!! (Tahitian for Sail, Sail, Sail Away!) On the omen of a rainbow in the west, the Tavaru fleet departing for Rarotonga…

2 Comments

Cabana Boy

July 1, 2010Finding your way through safe passages…..

Dave Rich

July 7, 2010Liz,,

Awesome post! My buddy and I are horribly obsessed with multihulls and I love traditional sailing canoes. I plan to build/buy something similar when I return from exploring central america in a few years. I almost purchased a 38′ Cross trimaran to take to sea before I decided to drive but I felt that working another 4 years to get her outfitted just wasnt in my time frame.

Are you familiar with the works of James Wharram? Beaaaautiful Polynesian sailing canoe designs!!! Another small boat designer is Gary Dierking in NZ. Check out some of their work.