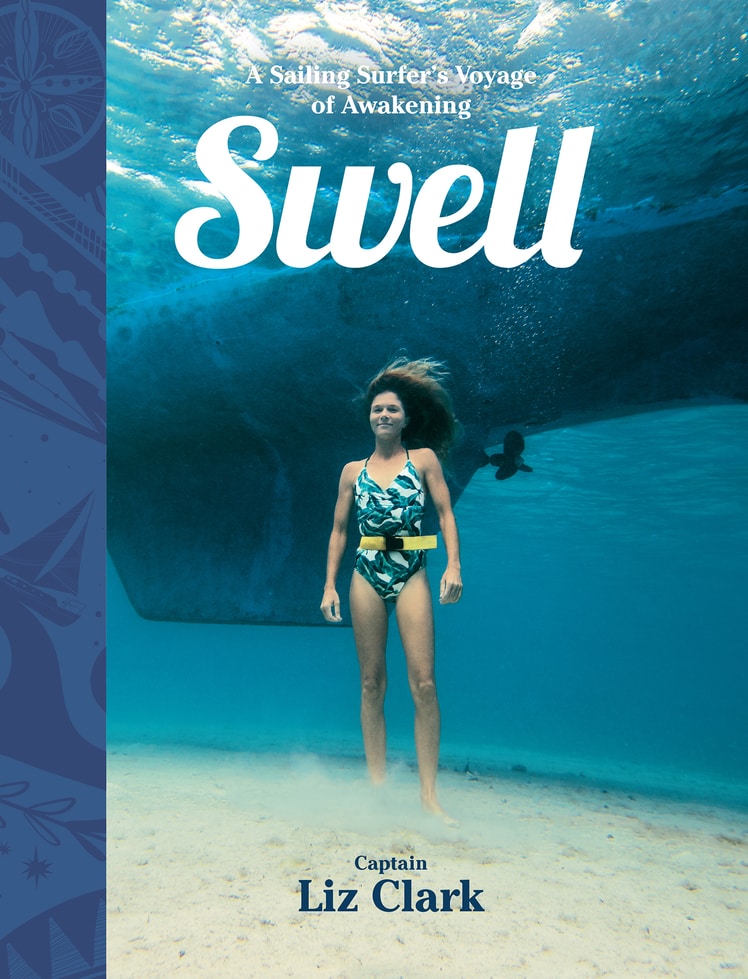

Footloose with the Hang-Out Gang

With the tube on the way and an expert installer ready to help, I fell into an easier rhythm in the V.I.P. yard. Between work on my book and other Swell ‘life-enhancement’ projects, I tried not to resist my situation and enjoy the good around me. I greased winches, worked with Olivier to flatten the floors in the galley, made an extension for the mid-cabin bunk, and refinished the countertops.

Just outside the chain-linked fence that surrounded the yard, the kids of the surrounding neighborhood flocked, squealed, bumped music, rode bikes, and hung out under the coconut trees. It was Tahiti’s ‘spring break’ of sorts, and hordes of younsters ranging from 7-20 years old, milled and chilled around the yard to the great displeasure of the yard owner . Ever since I’d let them borrow my skateboard and started playing soccer in the afternooons, they’d stopped calling me ‘madame’ to my great relief and would now scream ‘Leeeeeeeez’! whenever I surfaced from Swell.

These kids were tough and hard, but deep down they were all good kids. There were no afterschool programs or camps, they knew only street rules of kid-on-kid survival—teasing and talking was part of the game. They’d fish off the jetty, climb trees for fruits, ride bikes, sell fruit to boatyard clients, and constantly harass each other. When the sun sunk low enough for the day to cool a bit, the scattered groups of kids would come together on the 40 yard stretch of asphalt between the main road and the boatyard entrance gate—the day’s feuds, events, crushes, and quarrels were played out in the daily evening soccer match.

It was half indoor, half outdoor soccer. The ‘indoor’ side was the fence surrounding the ‘V.I.P. yard’ entrance, which had been made extra challenging by the yard owner who lined it from top to bottom with barbed wire to deter the kids from playing there. The ‘outdoor’ side was just opposite, where the road fell into a drainage ditch and then an open terrain. Teams fluctuated in numbers and skills. It was girls, boys, women, and men of any age. No shoes, no jerseys, no referees, but street rules and common courtesy kept the game flowing much better than one might imagine. No one kept score. Newcomers would watch for a moment from the sidelines to determine the dominant team and then join forces on the weaker side.

I had wanted to play with them for awhile, but felt shy to join in. Then one afternoon I had waited too late to go surfing my body badly need some exercise. I could see the kids running and hear their shouts from Swell’s dusty deck. Finally, I wandered out the gate and asked, “Can I play?”

“Oui!” They said. “You go that way!” Jay, the Rae-Rae, pointed. He became my overseer and language coordinator in the following weeks. Soccer became my release. The kids were the light in my daily grind. When the surf was mediocre, I’d wander out the gate, filthy and barefoot, to sprint back and forth on the asphalt until it was too dark to see anymore. Some of the kids didn’t accept me right away, but eventually they all got used to the grungy ‘popa’ (equivalent to Hawaiian ‘haole’) who ran fast but lacked any real ball-handling skill.

I dissolved into these evenings, whether the clouds poured down rain or the sunset ignited the sky above us, I felt grateful for the damp asphalt, the half inflated ball, my calloused feet, the warm salt-laden air, and the giggling, shit-talking, glowing Tahitian faces that were now all friends.

2 Comments

Todd Bates

April 20, 2010You make me laugh and smile. My son is 14 and running track as I write this. I can only hope that he has half the adventures that you do.

steve rupp

April 21, 2010You, young lady, can write. Thanks